I have previously worked with VE Commercial Vehicles in their after market domain. I was a Supply Chain Analyst there under the disguise of Demand Planner. One fine morning, when my head called me into his cabin, he asked me about the status of Inventory.

When Heads inquires about something, they usually know the answer in advance. The status of inventory was not really good. Our entire team was under pressure and this is why I was being questioned.

“So, why is the inventory levels high this quarter? Facing some challenges with the planning?” He asked.

“Not really, sir. I had raised the levels of stock at our warehouse since the guy at dealerships has raised the levels. Maybe the outcomes of those is showing the inventory level high but we’ll soon roll out,” I completed.

“Or maybe you have kept the stocks a bit higher?” He smirked, rubbing his chin.

“Umm.. i have kept 50% of their stocks so I don’t think so..”

“50%? You mean, if they are keeping 100 shafts, you are going with 50? Make it 35!” He snarled this time.

Well me being the rookie in the game couldn’t understand this move. I mumbled, “Isn’t 35 too little to serve their orders?”

He smirked once again, “Have you even seen the wave of bullwhip when splashed? C’mon take a marker and draw a one on board!”

I drew the one.

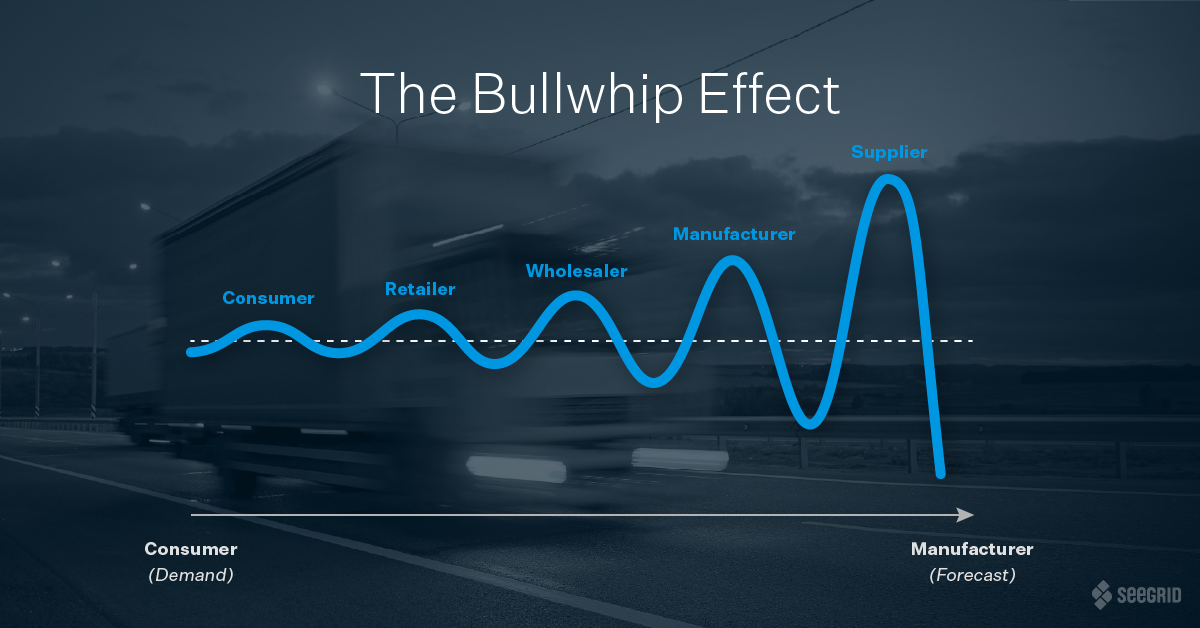

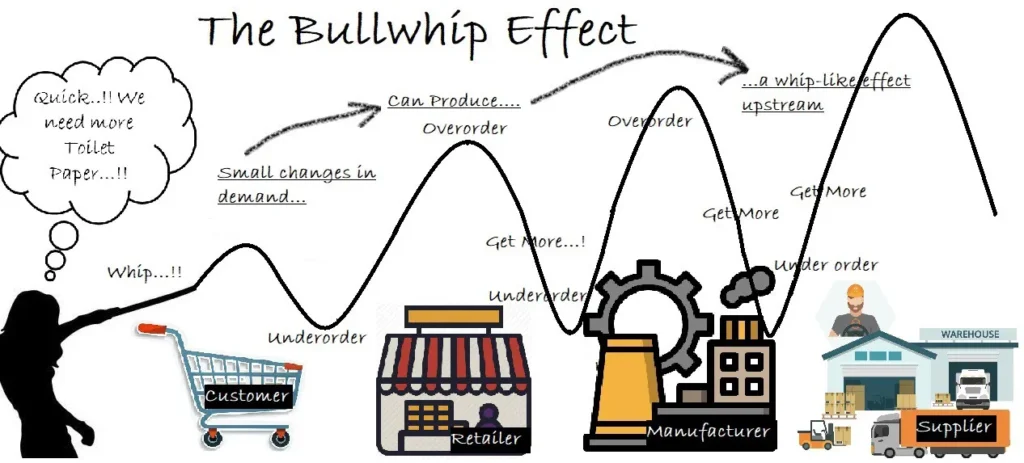

He was satisfied with the diagram and then asked me to label the holding hand as ‘Customer’ and the free end as ‘Supplier’. The others between were labelled as ‘Planner’→ ‘Buyer ’→’Manufacturer’ in the order and final diagram came out to be something like below:

He was satisfied with the diagram and then asked me to label the holding hand as ‘Customer’ and the free end as ‘Supplier’. The others between were labelled as ‘Planner’→ ‘Buyer ’→’Manufacturer’ in the order and final diagram came out to be something like below:

The above picture shows the distortion in orders. A customer order 50, the distributor takes buffer and orders 80, planner goes with 100 further while manufacturer asks supplier for 150 orders raw materials. This is how a order of 50 becomes 150 in upstream supply chain. This entire distortion in order is nothing but ‘Bullwhip Effect’

As per Wikipedia, the Bullwhip Effect is a supply chain phenomenon where orders to suppliers tend to have a larger variability than sales to buyers, which results in an amplified demand variability upstream.

The concept first appeared in Jay Forrester’s Industrial Dynamics (1961)[1] and thus it is also known as the Forrester effect.

Coming back to our story, I actually realised why 35 was important over 50 and how 50% of his orders was creating a distortion in orders and further a pressure on our inventory levels too. I changed my methods, keeping in mind the bullwhip effect and a month later, our inventory levels were in so much control.

Shoot in the comments, if you want more such discussions!

I’m sure you don’t want to receive this mail in your spam! So, if it’s so, please go through spam, and select the mail. A window on the top right corner will pop up, click on “Move to” and select “Primary”. There you go, you’re part of the newsletter now 🙂